GUKURAHUNDI REVISITED

Memories of a massacre

stand first: The Guardian's correspondent in Zimbabwe in the early 80s, NICK WORRALL, gives his exclusive first-hand account of how he broke the news of the Gukurahundi massacre in Zimbabwe.

'Dozens of small villages had been similarly attacked and hundreds - possibly thousands - of people shot dead'

'My colleagues had betrayed our confidence and agreement'

'The suffering people of Matabeleland were failed miserably by the journalists'

'The Catholic Church knew at first hand about the killings and had been giving fleeing villagers places of refuge in their churches'

It was a quiet Saturday morning in January 1983. I was sitting reading the sparse newswires, sitting at my desk in the small office I rented in Frankel House, in the centre of what used to be called Salisbury - now Harare. There seemed little news around on this sultry day and my mind was drifting towards swimming pool and cold wine.

So, about to leave for home, I was picking up some papers when a small, oldish man, entered my office. He looked dishevelled and out of breath. He thought mine was the BBC office. I told him it was not but, sensing a bit of news, I asked him to sit down, catch his breath and tell me his story.

He told me he had rushed over from Matabeleland where something dreadful was happening and he wanted to give details to the BBC. I told him that the BBC correspondent was, as far as I knew, out of town. But if he could give me details I would see that it was passed to the BBC when their man returned. In the meantime I asked him to tell me what was upsetting him.

The story he stammered out turned my blood cold. I asked if I could come with him to his village so he could show me enough for me to give the story to my newspaper. The BBC, I said, would certainly pick it up quickly.

There had been quite a bit of news to report - government irritation at my claim (true as usual) that Zim, suffering from severe shortages, was getting its petrol, from South Africa. Tantamount to a shameful African crime at that time. Then there had been consistent reports from Matabeleland of attacks on farmers with official blame being aimed at "dissidents".

Some attacks, including a bomb or two in Harare and another against the air force in Gweru, were being blamed on the South Africans or perhaps on disgruntled former Rhodesian soldiers who refused to live under black rule.

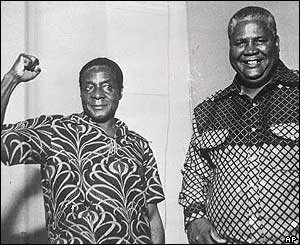

Apart from these Robert Mugabe had made an unexpectedly good start after his sweeping election victory in 1980. A certain amount of opposition had come from Joshua Nkomo's Matabeleland supporters, but a strong military presence in that part of the country seemed likely to quell any potential rebellion.

Most of the Zim armed forces had received training from the British army, but a curious decision, which was bound to irritate the West, brought in soldiers from North Korea to train a new element of the local forces - to be known as the Fifth Brigade. They already had the country agog after a major showing of drill, armed and unarmed combat at the capital's major soccer stadium.

I had arrived in Zimbabwe in 1981 to report for the London Sunday Times but I changed to the Guardian when I had the chance. I was fond of this great liberal paper from my days in Britain, especially since my father had been their man to report on Ian Smith's illegal declaration of independence in defiance of colonial masters Britain. John Worrall was expelled when Smith finally lost patience with his fair, but often damning, reports.

I decided that I should not go down to dangerous Matabeleland alone but pass the news to two other British correspondents, the Reuters bureau chief and the freelance stringer for The Times. We all agreed to go down together first thing the next morning.

My informant had come from a small village some distance northwest of Bulawayo. He took us there. All that remained was a ring of burned huts, some still smouldering. There were a few women. They were obviously in mourning. As we drove in they gathered up their children and moved away. But our friend called them back and reassured them that we meant them no harm.

They told the story that two days before a troop of Fifth Brigade soldiers had driven into the village and brandished a piece of paper. They read out the names of several men, all of them local officials of Joshua Nkomo's ZAPU political party. They ordered the villagers to produce the men. When they said the men were not in the village the soldiers grabbed six villagers, male and female. These were lined up in front of a hut and shot. Huts were then set on fire and the soldiers departed.

We were shown hollow graves in which the murdered villagers had hastily been buried. And we were told that this incident was by no means a one-off. Dozens of small villages had been similarly attacked and hundreds - possibly thousands - of people shot dead. Others, they said, especially young men, teenagers, had been savagely tortured with bayonets and left to die on the ground.

We were shown two or three more villages which had suffered a similar fate at the murderous hands of the red beret-wearing Fifth brigade. We saw more shallow graves, more burned huts and more weeping women. In each case the same story was told - they were seeking Nkomo supporters and were under orders to kill them.

We were also taken to the Mpilo hospital in Bulawayo where we were told many young men had been taken suffering from bayonet wounds. We saw about 15 victims, covered in bandages over a mass of holes in their chests and stomachs. Some were clearly in great agony, others had been drugged and were sleeping. Those that could speak told a similar story - they'd been dragged away from their huts or from their work and the soldiers had repeatedly stabbed them and then left them, lying on the ground.

When we had seen enough we retired to the Holiday Inn hotel to discuss what we had observed. It was now quite late on Sunday but there would be time to write a story and file it to London by telex that night. We were of the opinion that it was important that all three of us should tell the story now - in that case we would be protected by the coverage. No-one could accuse any one of us for having made up the story which seemed to accuse Robert Mugabe and his army of mass murder. There was safety in numbers.

The next day I discovered that the Guardian had used my story on the front page. Reuters and the London Times had printed nothing. My colleagues had betrayed our confidence and agreement. I knew that it was only a matter of time before I would to pay the same penalty as my father had 13 years before.

It was nearly three months before they expelled me. I spent time trying to get others who knew full well what was happening in Matabeleland to support me from the accusation that my story had been a lie. I travelled to Botswana where I found hundreds of refugees from Matabeleland in a camp, all of whom told similar stories of the massacre. The Catholic Church knew at first hand about the killings and had been giving fleeing villagers places of refuge in their churches. But no-one wanted to admit to the problems.

Another well-informed organisation was Oxfam who had several programmes for the poor in Matabeleland and had observed the actions of the troops. But they did not want to jeopardise their operations either.

One result of my report (which was never acknowledged by Mugabe or any other Zimbabwean official) was to have Matabeleland closed down to the press. It took more than a year before Donald Trelford made the effort for The Observer to look for himself. Not many of our colleagues have made that effort. Perhaps in future journalists might show a bit more courage when confronted with this kind of brutality. On another occasion lives might be saved. In this, the suffering people of Matabeleland were failed miserably by the journalists.

The role of the press over this dreadful issue was far from courageous, nor has it resulted in any repentance or admission of guilt and change of heart by Mugabe, himself a Roman Catholic. I shall never forget these words about his president from an embittered Joshua Nkomo during an interview: "Mugabe has dismantled everything but mantled nothing".

1 comment:

i am a gukurahundi orphan. It is heeling to hear my past being told. My fellow Shona counterparts deny all this on behalf of Mugabe. They dont think that it was real!!! To them its a fake story ...but yu cannot call the death of my parents fake!!!

Post a Comment